"Could Magic Mushrooms Be Medicine?"

With over 50 years as an illegal drug, can psilocybin mushrooms take a new role in UK mental health?

Back in February this year, six billboards were set up around London, each with a QR code and a single question: “Could magic mushrooms be medicine?”

The code would link to a site that would then ask people to share their stories of using the psychedelic drug.

🍄 COULD MAGIC MUSHROOMS BE MEDICINE? 🍄 Today @PAR_global_ launched the UK’s first psychedelic ad campaign asking the public to support #PAR for researchers! Check it out at 6 sites across London! Congratulations to @austint @Rosie_Psi and the gang! #psilocybin #psychedelic pic.twitter.com/1UAhmnIkx3

— Timmy Davis (@TimmyJSDavis) February 13, 2023

In late 2022, a petition was also made on the UK parliament site for moving psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in this type of fungi, to Schedule 2 of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001.

Both events were at the hands of a campaign called Psilocybin Access Rights (PAR), a volunteer group whose sole aim is to revamp the research scene of psychedelics by stripping their associated stigmas.

“Our laws are based on nothing more than a quirk of history.”

Psilocybin has been proven medically to help people overcome mental health challenges. Evidence also shows that it creates nicer, more law-abiding people which could ultimately lead to reduced violence and crime. #PAR pic.twitter.com/SzHvJzXEfB

— Paul Stamets (@PaulStamets) September 23, 2022

The UK has two main bodies of law which prevent psilocybin from being a widely used drug. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 keeps them from being legally possessed, sold, or consumed in any sense of the word.

As for the 2001 regulations, mushrooms remain in Schedule 1, which is considered to have no therapeutic value whatsoever.

Source: Psilocybin Access Rights

Source: Psilocybin Access Rights

In other countries, this isn't the case. Starting July 1, 2023, Australia will allow the prescription of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. In other words, this will be an attempt to help people who have a more complex to treat form of the condition.

Movements in the UK have pushed for advocating a change in the longstanding restrictions from these drug laws, and to catch up with the other nations who are pioneering new forms of therapy.

The harsh truth, however, is that campaigns have to climb the political ladder in order to make any influence for rescheduling psilocybin.

An example of this can be seen with the Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group (CDPRG), a think tank that was set up in 2019 by Crispin Blunt, a Conservative MP.

“We just call ourselves conservative with a small “c” because they're in power and they're the most traditionally averse to drug policy reform. You could try to change the minds of the Greens, but they wouldn't be able to do anything about it and they're already on board,” said Timmy.

“It’s the most conservative department of the most conservative party in British politics in possibly the most conservative country in the Western world.”

Timmy Davis, 31, joined in late 2019 as the CDPRG’s psilocybin rescheduling project manager. He is also the policy director for the PAR campaign and offers psychological support for the treatment-resistant depression trials happening at King’s College London.

A tied-in theme between each of the roles Timmy operates is allowing others to understand the role in which psilocybin operates in a clinical setting.

“People talk about this idea of a “magic bullet” or “silver bullet.” Sometimes they mean it's a “one shot kill”, where you just take one psilocybin dose and then you are cured of depression or your trauma has gone forever."

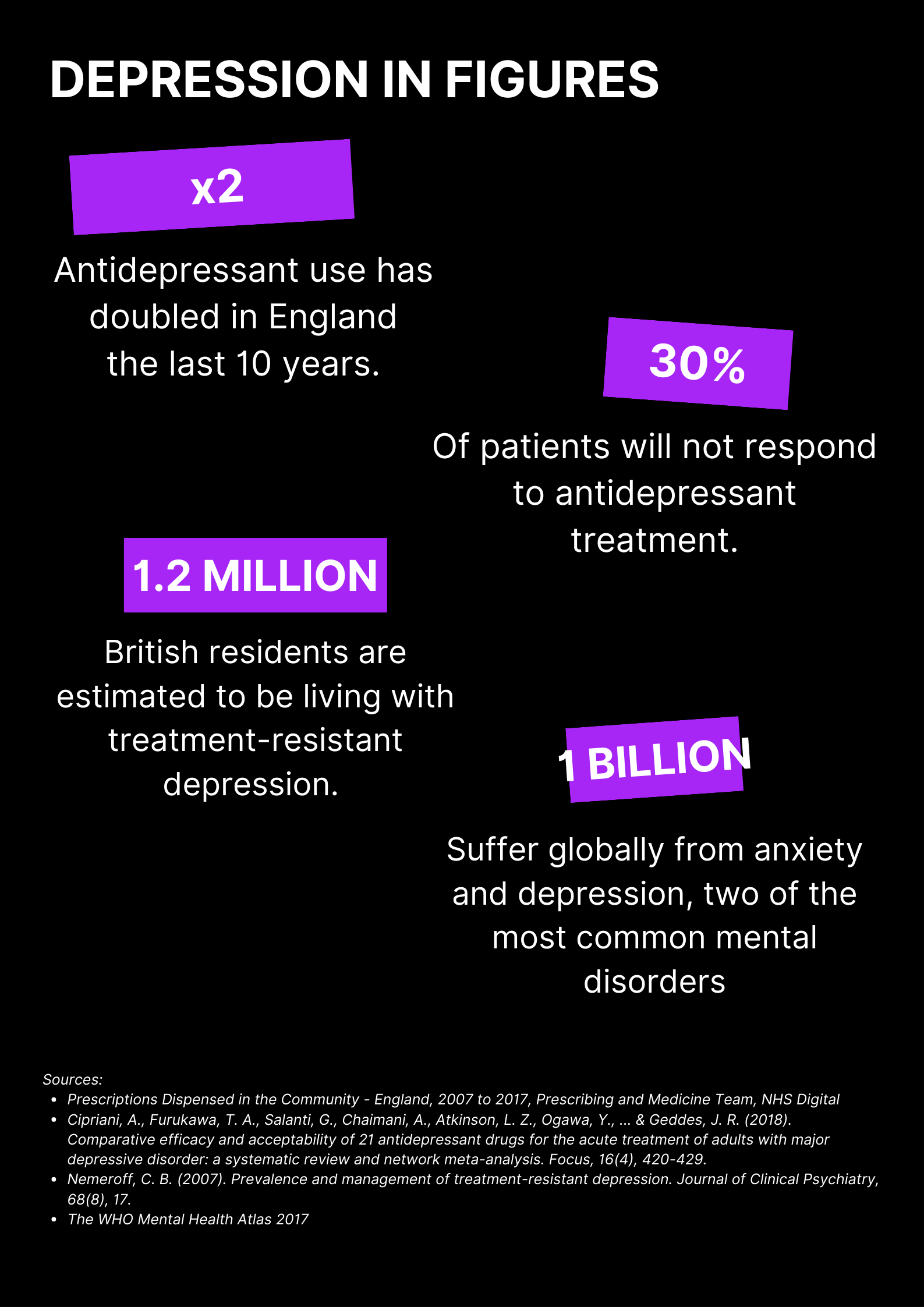

With antidepressants like SSRIs being widely used throughout the UK and other nations over the last fifty years, there is a conditioned expectation to have drug therapy work universally, rather than being bespoke to the individual.

A counter to this is that psychedelic drugs offer to fill in this void.

“They change the brain in such a way that a window opens where problems can be addressed and thought about in entirely new ways.”

Despite these views, its legality and potential for medical use continue to be absent.

To understand why the UK has such strict regulations on psilocybin would be to find out the history of the drug.

Looking further down the line, it seems magic mushrooms played a massive part in early humanity, had its cherished renaissance in research, and were then snuffed out quickly.

Tanzania | Australia

>10,000 B.C.E.

Rock art of Sandawe (A) and Bradshaw (B) cultures - By Jack Pettigrew

Rock art of Sandawe (A) and Bradshaw (B) cultures - By Jack Pettigrew

Even with over 6,500 miles between Tanzania and Australia, both countries share ancient rock arts depicting "mushroom-headed" people.

Made by the Sandawe and Bradshaw cultures, their Shamans claim each were created with the use of psychadelics.

Jack Pettigrew, a neuroscientist from the University of Queensland believed the two show their own experience of a trance under magic mushrooms and other hallucinogenic herbs.

Spain

4000 B.C.E

Ancient artwork featuring fungi - Photograph by Alan Piper

Ancient artwork featuring fungi - Photograph by Alan Piper

The work of post-Paleolithic rock art at the Selva Pascuala mural in Spain shows mushrooms resembling some found near the cultural site even today (Psilocybe hispanica).

Researchers believe their purpose was found in religious rituals around 6,000 years ago, making them possibly the first direct evidence of psilocybin use in prehistoric Europe.

Mexico

1957

Wasson (right) is handed mushrooms by curandera (folk healer) Eva Mendez (left) - Photo by Allan Richardson.

Wasson (right) is handed mushrooms by curandera (folk healer) Eva Mendez (left) - Photo by Allan Richardson.

Mesoamerican history showed psilocybin being used by its people up to thousands of years ago. The West rediscovered magic mushrooms thanks to two Americans who traveled to Mexico in the 1950s.

Robert and Valentina Wasson's journey to the village of Huautla de Jiménez was met with the Mazatec people, who were found to use psilocybin for their mind-altering effects in rituals.

Robert wrote his accounts of the experience, which would later be published in the American weekly LIFE magazine.

"Seeking the Magic Mushroom" would become a catalyst for drug culture movements in the following years.

1971

United States of America | United Kingdom

As psilocybin and other drugs started being linked with the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s, a ban on psychedelics was issued by the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

The UK government followed this with the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. The possession, distribution, or use of drugs listed by the government would become punishable by a fine or prison sentence.

The severity of the crime would depend on what class each drug was in. Psilocybin would be issued class A status, the highest level of the three.

Switzerland.

1997

Forty years after the LIFE magazine article was published, the University of Zurich began research on the effects of psilocybin, along with several other countries during the 1990s.

Their data not only found an increase in brain activity, but potential to treat a number of psychological and physiological conditions.

United Kingdom.

2005

Before 2005, psychedelic fungi and growing kits could be found for sale in areas like Notting Hill, west London, where one company openly advertised a variety to choose from.

This was due to the 1971 Act containing a loophole, which stated any mushrooms prepared or created were illegal, but so long as they were fresh, no offense was committed.

As a result, the Drugs Act 2005 amended the existing legislation, leaving them completely illegal, regardless of their state.

As for the future of magic mushrooms, Timmy is adamant the benefits will outweigh the setbacks.

“As people get more access to these medicines, these experiences, and the relationships to help navigate them, there’ll be ripples beyond just the treatment effect on a single individual. That's my hope, at least.”

Asking for public opinion through their petition and billboards gathers the necessary data for PAR to conclude what the British public wants out of psychedelics.

Their long-term goal, however, is to find out whether the UK is ready to accept psilocybin as a recreational drug.

“What if I don't have a diagnosis of depression, but I still want to access psilocybin in a safe and supported way? Or if I want to do it as a sacrament or at a music festival or for whatever I please.”

“When psilocybin does get rescheduled and people have access through medicine, then we can start to ask the question “could magic mushrooms be more than medicine?”

To get involved, visit: https://www.par.global/

For background images: https://www.pexels.com/